Behind the Scenes of Advanced Adversary in The Middle Techniques

By Bob and Rutger on (Updated: )

Phishing remains a very relevant attack vector used in the wild. Up to 60% of initial access methods rely on phishing, as recently published by the European Union Agency For Cybersecurity. During red teaming assessments, it is also a commonly used starting point. We’ve both spent a lot of time researching how (simulated) attackers protect their infrastructure against the prying eyes of investigators, SOC analyst and a range of automated crawlers. With this blog, we kick off a new series telling the tale of how we try to stay under the radar while keeping our SecOps under control.

Note that this will not be a how-to-phish manual. We will not go into detail about how and where you can actually purchase and create your infrastructure. We will focus on how an attacker can limit the amount of scanning activities on our system, and highlight indicators usable during analysis. Let’s dive in!

Objective

During an assessment, our starting objective is fairly simple, we want to gain access to a high privilige account from company X. To achieve this we can make a few choices on how we want to target them during our campaign. For example, we can try:

- TOAD (Telephone-Oriented Attack Delivery)

- AiTM (Adversary in The Middle)

- Device code phishing

- And many more..

Denpeding on the chosen method, multiple delivery methods are possible like e-mail, LinkedIn, teams or other chat messages. After we’ve sent our initial message, we hope to convince the target (using our awesome social engineering tactics) to visit one of our beautiful websites, where we will attempt to steal their credentials.

However, as always, there is a challenge to this approach. In the modern internet, the moment we release a new website it will be scanned and evaluated constantly. Not only by “respected” bots, who are nice enough to indicate that they performed the scanning activity. Of course you can influence legitimate crawlers using the robots file, but security-related scanners (whatever their intent) tend to ignore those guidelines.

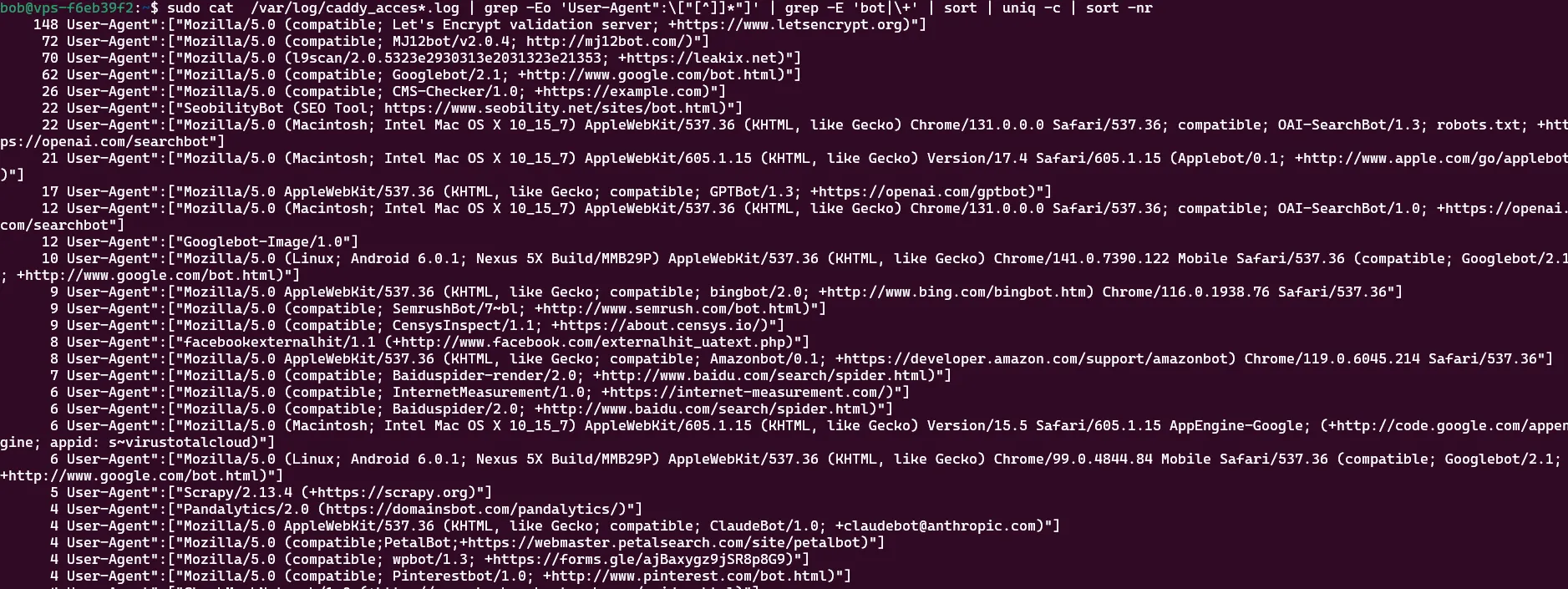

So, after purchasing a domain, bringing it online and doing absolutely nothing with it (except creating a Lets Encrypt server certificate), we took a look at the logs to discover quite a few pesky visitors:

Note: If you’re using caddy, you can use the handy oneliner below to get the same result:

sudo cat /var/log/caddy_access.log | grep -Eo 'User-Agent":\["[^]]*"]' | grep -E 'bot|\+' | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

Note that these are only the user-agents that mention they are a bot. So, imagine what happens when we do actually start using the domain actively. We don’t want our assessments to be detected before we have even started, or even worse, gets taken down! So, we need to put defenses in place to give us more time until the companies detect our server and request a takedown.

So, lets revise our goal a bit! We’re going to try to block investigators and crawlers while keeping our infrastructure available for our (real) target audience. While improving our infrastructure, we will also review and share defensive strategies.

Finding the right target

One of the first things which we want to accomplish is that we show meaningless content for all visitors which are out of scope, as a distraction. We actually don’t intend to block scanners or other security providers or send them away. We just want them to think that they’re looking at a plain old website and nothing phishy is going on. Blocking or redirecting them would be a strong indicator something strange is going on, which could merit further investigation.

To accomplish this we need to show them somewhat convincing, real content. We only intend to show the real landing page to people if (at least some of) have passed our checks. In a follow-up post we will get into the details about how we do this, but as a first taste, take a look at the following examples, which help determine if you’re a real visitor.

Note: Of course, you could also opt in on using a turnstile from Cloudflare or any other (invisible) captcha system, they offer great anti-bot detection capabilities. However, during an assessment we are not that fond of sharing our infrastructure with such big organizations. We also noticed these systems do add a visible delay to the page. Instead of a quick passthrough, visitors were stuck on our lures for multiple seconds. When performing type squating attacks this is exactly what you don’t want!

Example A - Quishing Campaign

During a Quishing-campaign (QR-code phishing) we expect mobile phones only, seeing a “physical” image has to be scanned. Hence, it would make sense to verify that our visitors are actually using mobile phones. There are many techniques which can help verify this, for example:

- Verify the user agent that it contains Android, iPhone iPad or iPod or Mobile.

- You could validate the navigator property for maxTouchPoints.

- Is the viewport small? Normally the viewport on a mobile phone has a limited max-width.

- Is hovering supported? It should not be. You are using your finger, not a mouse.

Of course, the above are just some examples. But if multiple of these are not correct, then we could assume that our visitor website isn’t using a mobile device and therefore should not be able to view the real content.

Example B - A Dutch Company

If we are performing an assessment on a Dutch company, is it logical that a visitor is communicating with us using a different character set then the one commonly used in the Netherlands? In some browsers, using JavaScript, it is possible to extract the keyboard layout information. The used character set can be used to help verify a visitors country, because there are some minor, but very specific differences between some character sets. For example, take a look at the following table:

| Key | Dutch | Estodian | United States | Belgium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semicolon | + |

ö |

; |

+ |

| BracketRight | * |

õ |

] |

* |

| Backquote | @ |

ˇ |

` |

@ |

| BracketLeft | ¨ |

ü |

[ |

¨ |

Or does it make sense that the visitor is in a completely different time zone located in the United States or Asia? Aside from browser settings, which are configurable by definition, you could also peek at the visitors properties which are harder to spoof like their IP or ASN (Autonomous System Number). More on that later.

When a real visitor visits a web page, they leave a pretty clear fingerprint of where they are. When an autonomous scanner visits the same page, properties often do not match and create an invalid picture.

Example C - Are You A Browser

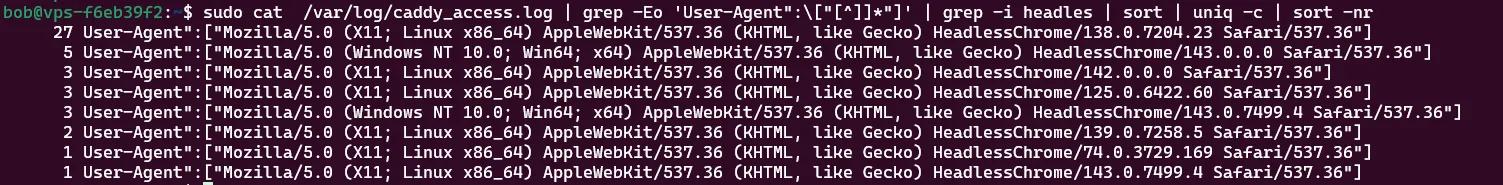

During the communication between a client and a server, a lot of potentially identifying characteristics are up for grabs. These characteristics can be used to filter out traffic from clients which are clearly not using a “real” browser, for example:

- A headless browser: used by many crawlers.

- Python: used in a lot of automation.

- Manual fetching with curl, wget or sortlike tooling.

sudo cat /var/log/caddy_access.log | grep -Eo 'User-Agent":\["[^]]*"]' | grep -i headles | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

There are other characteristics that can be combined into identifiers like JA4 and JA4H. For example, during our research we learned that across multiple browsers and operating systems that the JA4_A header is quite static, and that they often communicate using TLS 1.3 over HTTP 2.0.

Another strong indicator is the cipher suite count: with real visitors this is almost always between 15 and 17 supported ciphers. If we test with tools like curl and wget many more cipher suites are communicated, for example:

- 90 cipher suites for

curlon Kali 2025.04. - 31 cipher suites for

curlon Ubuntu 24.04. - 20 cipher suites for

curlon Windows 11. Getting close right? Well, no. It communicates using HTTP 1.1 instead of the expected 2.0!

During our research we’ve performed an analysis for different programs and their JA4 values, which we will discuss in an upcoming blog post.

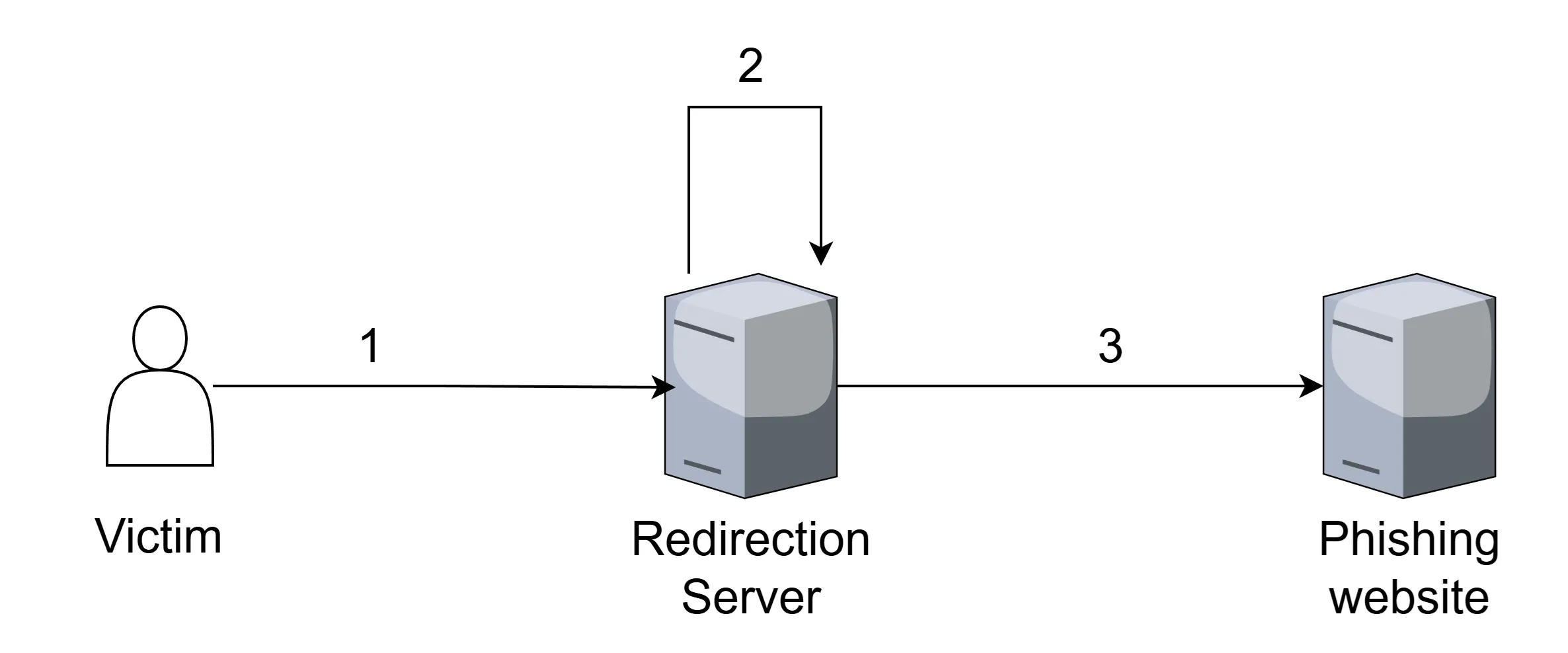

Content Hotswapping

After we think we can make a somewhat strong estimate of who our visitor is, we can determine what to do with them. And that is where the next interesting part comes in, content hotswapping. Based on who (or what) we think you are, our server starts serving different content using the same endpoints. If we think you are a crawler or scanner, we want to server you a convincing (and pretty) web page. But, if you somehow magically pass all of the following example checks:

- The client we are communicating with looks like a browser.

- It looks like a mobile device.

- It is from our targeted area.

- A specific endpoint is visited.

- It is accessed in the specific time range we expect (only the SOC works in the weekend, right

:)?)

So at this point we’re pretty certain you’re a real visitor which is allowed to see the real deal, and the server presents you with the actual phishlet! Of course, we will go into (a lot) more detail later on.

Infrastructure

Of course, at this stage the visitor logs into our very convincing authentication page and we are given access to your session. This session may be limited to a single application, but in the case of SSO (like the Microsoft login portal), this would entail access to all linked applications. There are some great defensive measures which can (and should) be implemented to help protect against these attacks like conditional access or fido keys. More on that later!

This Is The End

While the above doesn’t contain many technical details, keep the following in mind: From a defensive point of view, you shouldn’t trust what you see. For example, in a SOC people tend to rely on the output of sandboxed scanners. These scanners run real browsers (so they do earn some points), but they run from illogical (physical) locations. Remember who you are protecting and try to mimic their behavior as best as possible when analysing an endpoint.

Anyhow, as mentioned, this is the end. For now. In next posts we will explore the following subjects:

- Custom fingerprinting: how do we estimate if a visitor has a real browser?

- Testing the browser: how do we verify you browsers’ capabilities?

- From lure to phishlet: protecting what we know about a visitor.

- Hotswapping content: how we create dynamic content based on who we think you are.

- Defence, defence, defence: combining all our lessons learned, what can you do against this?

Thanks for reading, and see you soon!