Testing Ports For A Reverse Shell

By Rutger on (Updated: )

Ever had that moment where you’re having a blast on a platform like HTB or THM, and you’re pretty confident you can set up a reverse shell, but you just can’t figure out which remote port to use? When I’m practicing, I often default to reusing the port I’m using to send the shell or pick something less common, like 9001. But sometimes, you need to think outside the box and get a bit more creative.

Since I don’t like manually testing 20 ports, I’ve automated parts of this process into something I like to call a ping pong test.

On my own host, I run a series of basic python TCP listeners for a collection of common ports. When the listener is called, the server logs the requestor IP and its port. Finally, it sends the word pong.

On the target machine I try to contact my host on the same list of ports, in this context this is the ping.

If we’re lucky, at least one of those outgoing connections is allowed through the firewall and other defenses in place.

Pong - The listener

The following, non exhaustive, list of common ports is used in my example scripts. Note that port 80 is not included, in most scenarios I’m running Apache on my host to serve files and exploits. The list should be tailored to your system, services which you’re already running (e.g., FTP or SSH) should be excluded to avoid conflicts.

| Port | Protocol |

|---|---|

| 21 | FTP |

| 22 | SSH |

| 23 | Telnet |

| 25 | SMTP |

| 53 | DNS |

| 67 | DHCP |

| 88 | Kerberos |

| 110 | POP3 |

| 139 | NetBIOS |

| 143 | IMAP |

| 179 | BGP |

| 443 | HTTPS |

| 445 | SMB |

| 636 | LDAPS |

| 1433 | MSSQL |

| 2483 | Oracle DB |

| 3128 | Squid Proxy |

| 3306 | MySQL |

| 3389 | RDP |

| 8080 | Alt HTTP |

| 8443 | Alt HTTPS |

The Python script is pretty rudimentary. For the given set of ports, it sets up a TCP listener. It has almost no error handling, and as stated before, its only purpose is logging requests and returning pong.

import socket

import threading

import sys

def pong(client):

""" Attempt to send 'pong' to the client """

try:

client.sendall(b'pong')

except Exception as e:

print(f"[*] Failed to send pong to {client}")

print(e)

finally:

client.close()

def start_listener(port):

""" For the given port, set up a TCP listener. On each incoming connection, log the client details and current port. """

server = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

server.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

server.bind(('0.0.0.0', port))

server.listen(5)

while True:

client, addr = server.accept()

print(f"[+] {addr} on port {port}")

handler = threading.Thread(target=pong, args=(client,))

handler.start()

def main():

ports = [21, 22, 23, 25, 53, 67, 88, 110, 139, 143, 179, 443, 445, 636, 1433, 2483, 3128, 3306, 3389, 8080, 8443, 9001]

threads = []

for port in ports:

listener = threading.Thread(target=start_listener, args=(port,), daemon=True)

listener.start()

threads.append(listener)

try:

for thread in threads:

thread.join()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\n[*] User aborted. Exiting")

sys.exit()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Ping - The client(s)

Below I’ve written out 5 examples on how to test the outgoing connection using different languages. But before testing any of them, I had to block a few remote ports (445, 555 and 3389) on the Windows virtual machine in my lab:

# Block remote ports 445, 555 and 3389

New-NetFirewallRule -DisplayName "fw_block_example_445" -Direction Outbound -Protocol TCP -RemotePort 445 -Action Block

New-NetFirewallRule -DisplayName "fw_block_example_555" -Direction Outbound -Protocol TCP -RemotePort 555 -Action Block

New-NetFirewallRule -DisplayName "fw_block_example_3389" -Direction Outbound -Protocol TCP -RemotePort 3389 -Action Block

# Don't forget to remove the rules after testing:

Remove-NetFirewallRule -DisplayName "fw_block_example_445"

Remove-NetFirewallRule -DisplayName "fw_block_example_555"

Remove-NetFirewallRule -DisplayName "fw_block_example_3389"

During the testing of below examples I have only included a few ports, of which most are blocked to prove my point.

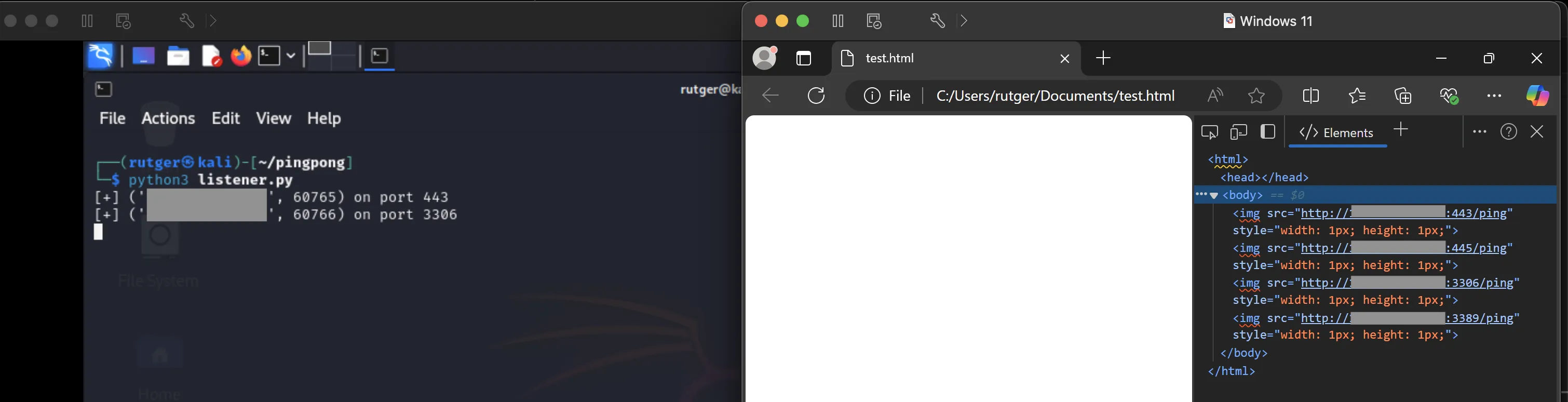

Example 1: HTML

The first example is written in HTML. In a few examples I’ve encountered exercises where a HTA file could be uploaded or mailed, and this gives us a potential way to test ports before starting a shell.

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

<img src="http://10.0.0.1:443/ping" style="width: 1px; height: 1px;" />

<img src="http://10.0.0.1:445/ping" style="width: 1px; height: 1px;" />

<img src="http://10.0.0.1:3306/ping" style="width: 1px; height: 1px;" />

<img src="http://10.0.0.1:3389/ping" style="width: 1px; height: 1px;" />

</body>

</html>

As seen below, the remote ports 443 and 3306 are reached by opening the HTML page, but 445 and 3389 are not. Nice!

Example 2: JavaScript

Of course, example one can also be achieved in pure JavaScript. This may come in handy when having access to a cross-site scripting vulnerability. Note that this can easily be blocked by correctly applying a Content-Security Policy to the web site.

const ports = [443,445,555,3306,3389];

for (port in ports) {

fetch(`http://10.0.0.1:${ports[port]}/ping`, {

mode: 'no-cors'

});

}

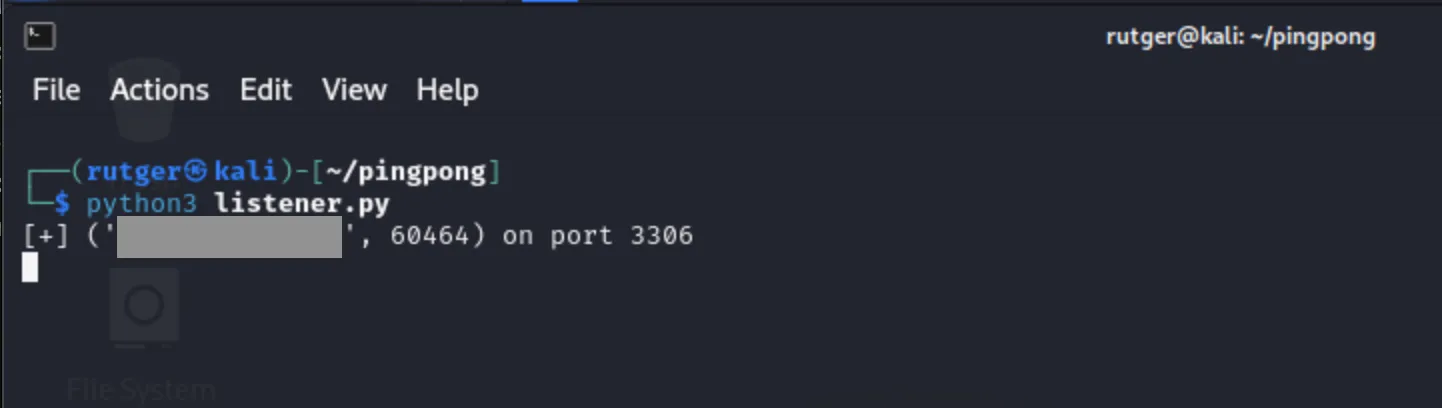

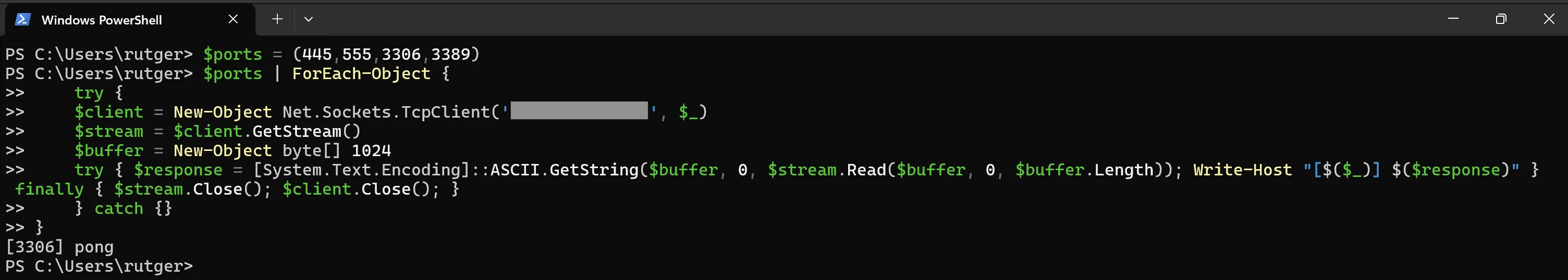

Example 3: PowerShell

While the easiest way to test the connection would be using a tool like wget, curl or Invoke-WebRequest, the following script is set up in a way that it can later be used as a base to automatically start a connection on the first received pong. It uses Net.Sockets.TcpClient to set up the TCP connection and reads the response.

$ports = (445,555,3306,3389)

$ports | ForEach-Object {

try {

$client = New-Object Net.Sockets.TcpClient('10.0.0.1', $_)

$stream = $client.GetStream()

$buffer = New-Object byte[] 1024

try {

$response = [System.Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetString($buffer, 0, $stream.Read($buffer, 0, $buffer.Length));

Write-Host "[$($_)] $($response)" } finally { $stream.Close(); $client.Close(); }

} catch {}

}

As noted before, I’ve blocked the remote ports 445, 555 and 3389. In this example, as shown below, I only see port 3306 being reached by the client.

And as you can see in the following image, the word pong makes its way back to the client!

Example 4: Bash

Using bash a likewise result can be achieved. This simple script loops through the list of ports and uses the binary nc to set up the connection. As in the PowerShell example, when pong is received, the related remote port is printed.

IP="10.0.0.1"

PORTS=(445,555,3306,3389)

for PORT in "${PORTS[@]}"

do

RESPONSE=$(echo -n | nc -w 2 $IP $PORT)

if [ "$RESPONSE" == "pong" ]; then

echo "[$PORT] $RESPONSE"

fi

done

Example 5: Legacy Windows Media Player

As a last fun example I want to link to an earlier post about fetching crafted files using the legacy Windows Media Player. Because this binary is able to fetch remote content, it can be (ab)used to test ports as well.

Of course, this tests if wmplayer is allowed to access the remote port. In a realistic scenario this wouldn’t necessarily mean every other application can set up the same outbound connection.

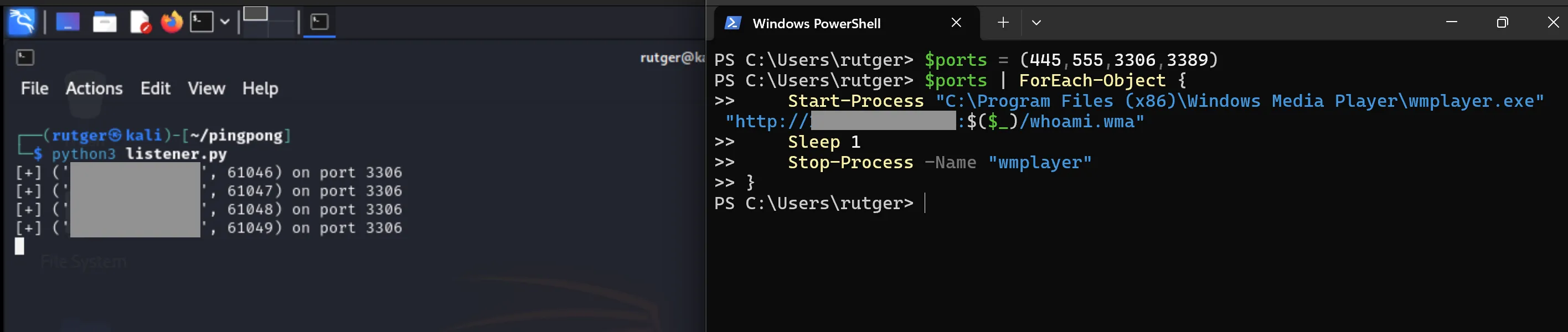

$ports = (445,555,3306,3389)

$ports | ForEach-Object {

Start-Process "C:\Program Files (x86)\Windows Media Player\wmplayer.exe" "http://10.0.0.1:$($_)/whoami.wma"

Sleep 1

Stop-Process -Name "wmplayer"

}

As seen below, wmplayer reaches the client multiple times on the open port:

Final words

I’ve enjoyed experimenting with these scripts. While they may be a bit noisy and messy, I hope they’ll prove useful in future exercises or penetration tests.